By Amanda Gronewold

When the COVID-19 crisis reached Mississippi and school buildings closed, teachers scrambled to find ways to continue delivering instruction to their students.

CTE teachers faced unique challenges compared to their traditional counterparts, including how to translate the hands-on learning required of many pathways to online learning. Three teachers from different pathways shared their stories with Connections.

Connecting Students to the Shop

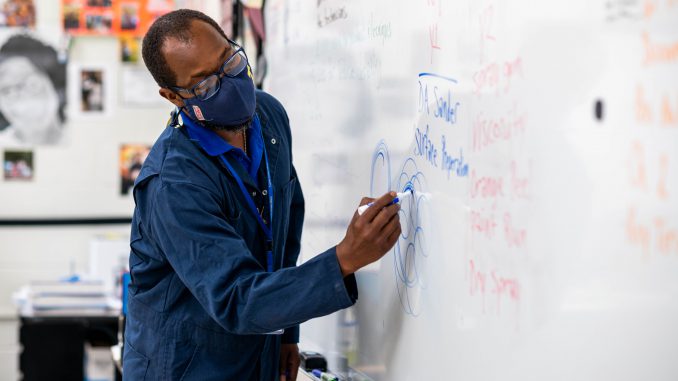

Tupelo collision repair instructor Derek Bradley had a daunting task: transforming a traditionally hands

-on shop class to one that could be replicated in students’ homes with little to no tools or materials. He relied heavily on online videos to demonstrate his lessons to students. Even before the pandemic, he enjoyed using them to make information more accessible.

“You never know what someone’s reading level is,” Bradley said. “And reading out of the book, they might not comprehend [the lesson]. But a lot of my students say, ‘If I see you do it, I can do it.’”

In addition to sharing videos, he sent packets filled with worksheets to students’ homes and experimented with online meetings. Meeting synchronously online proved to be difficult for students without reliable internet access, so he leaned even more into the videos, which were easier for students to view using smartphones. Among his favorite videos to share were those from the Collision Repair Education Foundation and collision repair YouTube channel CollisionBlast.

“I was just trying to get the hands-on knowledge as close as I could without the hands-on part,” Bradley said.

Some students even took on additional hands-on instruction while earning a paycheck and work experience. Bradley owns a collision repair shop in New Albany, and he hired several students during the school closure to keep them honing their skills. Automotive repair shops were considered essential businesses and were allowed to remain open.

This fall, Bradley used what he learned in the spring as he taught about half of his class in person and the others through virtual means. He shared videos and used the Canvas learning management system for all of his students, preparing his in-person students for a smooth transition to a virtual learning experience should another shutdown occur. Bradley also encouraged his students to connect with one another in social media groups with platforms such as Campus Knot.

“It’s going to be a smooth transition if it happens again,” Bradley said. “I post videos, and I record myself doing different things. I’m in the process now of taking pictures of their classmates that are here actually working on stuff, taking their safety tests and doing hands-on activities to connect the two as best that I can.”

The pictures mostly included a wrecked car in the class shop that will supplement several units of Bradley’s instructional content. As his in-person students received hands-on experience with the car, Bradley included his virtual class by sharing pictures of numbered sticky notes affixed to each area of damage on the vehicle.

“I can take and post the pictures and tell students to identify the parts in the numbers, and it’s the same thing that their classmates are doing in the classroom,” he said.

Bradley continues to work on ways to connect his virtual classroom with his in-person one. He has a large screen on which he broadcasts via Google Meet for a portion of the class time so all the students can interact before they break into in-person student groups to do hands-on shop work while allowing virtual students to complete the remainder of their work on their own time before a specified deadline.

“I’m just trying to see what’s going to work,” he said. “I’m trying a little bit of everything.”

Building an At-Home Business Learning Experience

When schools in districts with high poverty rates closed in the spring semester, delivering instruction in a way that is accessible to all students, regardless of internet access, became paramount.

Gary Harris, who teaches in the business, marketing and finance pathway at Crystal Springs High School (Copiah County School District [CCSD]), relied solely on worksheet packets to continue teaching his students for the remainder of the spring shutdown.

“Our district did not assume that all of our kids have internet access or computers, so we literally did everything by paper in March and April,” he said.

Harris created packets for his students from the textbooks and workbooks he already had. The district created pickup points throughout the area for families to receive their packets, as well as drop-off locations where they could return the students’ completed work. He provided links to YouTube videos as bonus material but did not grade his students on this content because not all students had internet access. Harris and other teachers attempted to connect virtually with students via Google Classroom with limited success.

“It was too much of a struggle for parents that didn’t have internet access, so that was a huge challenge for our school,” he said.

Harris’ community worked to overcome that challenge. As the shutdown continued, several businesses in the district began offering hot spots where anyone needing internet access could park and connect their device to a Wi-Fi network.

In the fall semester, his instructional delivery methods leapt forward technologically from where they were in the spring. He taught groups of students on a hybrid schedule that alternated groups attending in person and virtually to reduce crowding in the school. He only taught a small number of students who opted for complete virtual learning.

CCSD policy prohibits live broadcasting of lessons online due to privacy issues, so Harris delivered pre-recorded materials to his virtual students via Microsoft Teams. As his school’s hybrid semester unfolded, Harris and other educators prepared students to learn completely from home in the event of another shutdown.

“We are going to be more dependent on technology this point forward,” he said, “so we’ve been instructing our students on how to get signed into Teams, how to use Teams and how to complete assignments.”

Harris said he is optimistic his district is gradually improving its ability to deliver equal technology-based learning experiences to all its students. The district received funding from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act to supply students with laptops. Additionally, rural power associations in the area are building more internet connectivity spots.

“If this thing continues and we’re still using this method of instruction in January and February, it’ll be a lot more inclusive than it is now,” Harris said. “Even one student being left out is not ideal at all.”

Staying Ahead in Health Science

Millsaps Career and Technology Center (Starkville-Oktibbeha Consolidated School District) health science instructor Jemeica Arnold, who also works part-time as a nurse at the local hospital, has grown her technological aptitude in leaps and bounds since the pandemic began.

“I didn’t have any electronic communication for teaching at all. I was teaching mainly traditionally, standing up, lecturing,” she said. “I had to learn Canvas from the beginning and kind of build my Canvas classroom.”

By the time fall classes began, Arnold’s classroom experience went completely paperless, even for her in-person students. She pre-recorded all of her lectures at home and played them for both her in-person and virtual students.

“I’m really just a facilitator in the classroom. I’m not up talking and lecturing — it’s already pre-recorded, so that way the students at home are getting the same me in person with the PowerPoint, and then the ones that are coming traditionally are getting it on the SmartBoard,” Arnold said. “Everybody’s getting the same information.”

Arnold enhanced her students’ Canvas experiences with video-recording apps Loom and Screencastify. Even with help, student participation was a challenge, as many of her students were overwhelmed with as many as 10 courses — and their specific content — populating their student Canvas dashboards. Arnold offered Zoom office hours to provide her students extra help as needed and stressed to them the importance of working ahead.

Working with the future in mind is a crucial part of Arnold’s efforts to adjust to the newly overhauled health science curriculum while staying prepared for the possibility of future shutdowns.

“What I’m doing is going ahead and building the skeleton for those future curricula so when it’s time for them, all I have to do is plug the content in,” she said. “I’m trying to stay a couple of weeks ahead.”

Arnold’s expertise gives her a unique opportunity to teach her students about the pandemic and its implications in health care as it is happening in real time. She plans to discuss actual cases of the novel coronavirus in upcoming lessons with her second-year students.

“I’ll probably just wait until we get to employability and the rehab part and try to add some COVID-19 real stories to kind of help them understand some things,” said Arnold.

In many ways, the COVID-19 pandemic amplified already-occurring societal issues, with the lack of equal access to resources at home for all students being a prime example. Teachers, schools and districts are still working diligently to fill in these gaps. Teachers are also adapting to new technologies as they find ways to offer both their in-person and virtual students fulfilling learning experiences — learning as they go while preparing for challenges that could be on the horizon.